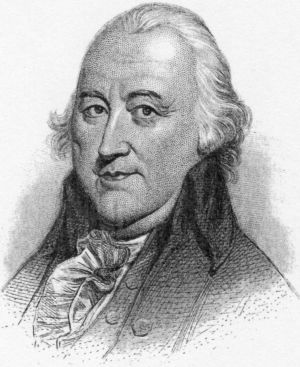

Primary Source

Artemas Ward writing to John Hancock to accept his Commission as First Major-General of the Continental Army

Head Quarters Cambridge June 30th 1775

Sir-

I have this Day rec'd your Favor of the 22nd in which you are so kind as to inform me of the general officers, that the Hon'[or]able continental congress have appointed.

I wish Sir, the appointment in the Colony may not have a Tendency to create uneasiness among us, which we ought at this critical Time, to be extremely careful to avoid.

I have Sir, to acknowledge the rec't [receipt] of the commission of a Major General & do heartily wish that the honor had been conferred upon a Person better qualified to execute a Trust so important. It would give me great satisfaction, if I thought myself capacitated to act with Dignity, & to do Honor to that Congress which has exalted me to be second in Command over the american Army. I hope they will accept my sincere Desire to serve them, & my most grateful acknowledgement for the Honor conferred upon me; & pray they may not be wholly disappointed in their expectations. I always have been , & am still ready to divote [sic] my Life, in attempting to deliver my native country from insupportable Slavery.

I am Sir, with great Respect,

Your most obedient

Humble Servant,

Artemas Ward

Quoted in The Life of Artemas Ward, The First Commander-In-Chief of the American Revolution, by Charles Martyn, (New York, 1921).