Primary Source

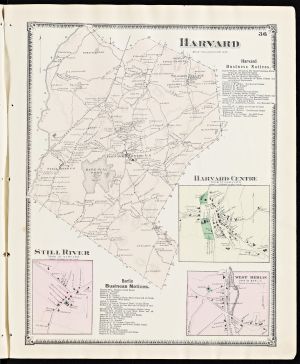

We have made an arrangement with the proprietor of an estate of about a hundred acres... For picturesque beauty, both in the near and the distant landscape, the spot has few rivals. A semicircle of undulating hills stretches from south to east, among which the Wachusett and Manadnoc are conspicuous. The vale, through which flows the Nashua, is esteemed for its fertility and ease of cultivation, is adorned with groves of nut trees, maples, and pines, and watered by small streams. Distant not thirty miles from the metropolis of New England, this reserve lies in a serene and and sequestered dell. No public thoroughfare invades it, but it is entered by a private road. The nearest hamlet is that of Stillriver, a field's walk of twenty minutes, and the village of Harvard is reached by a circuitous and hilly road of nearly three miles…. The present buildings being ill placed and unsightly, as well as inconvenient, are to be temporarily used, until suitable and tasteful buildings in harmony with the natural scene can be completed. An excellent site opens itself on the skirts of the nearest wood, affording a view of the lands of the estate, nearly all of which are capable of spade culture. It is intended to adorn the pasture with orchards, and to supersede ultimately the labor of the plough and cattle by the spade and the pruning knife...

From Bronson Alcott's letter to The Dial, June 10, 1843.