John Howe Spies on Concord, or Not

On this day in 1775, John Howe arrived in Concord to spy for British General Gage. He quickly gained the trust of the town's leading patriots. They took him to a storehouse, showed him the weapons stockpiled there, and dined with him. Howe recorded every detail in his private journal. The journal was published in the 1820s, and for the next century and a half, historians considered it a true account. There is just one problem: John Howe's journal was a hoax. In 1993 a skeptical scholar proved that if John Howe existed at all, he was not a spy for the British Army and that his journal was fabricated a half-century after the events it purports to describe.

Some Loyalists were ostracized; others were threatened with death, confined to house arrest, and, in the most extreme cases, tarred and feathered.

When New Hampshire printer Luther Roby published a 50-page booklet in 1827, he chose a title he thought sure to attract readers: The Journal Kept by Mr. John Howe While He Was Employed as a British Spy; Also, While He Was Engaged in the Smuggling Business. Roby explained in the introduction his belief that "Facts relative to the American Revolution, and to our late War [of 1812] will doubtless ever be interesting to the public." "Stories" would have been a better choice of words than "facts," since we now know that the journal is not authentic. We do not know the identity of the writer, but his motives seem clear: profit.

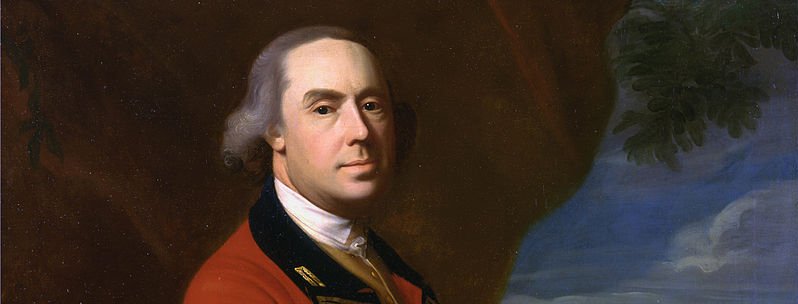

In February and March 1775, two British "spies" were out and about gathering information for their commander, General Thomas Gage. Ensign Henry De Berniere and a Captain Brown were studying the topography of Concord, the layout of the homes, streets, and bridges, as well as what supplies local Patriots were storing. The men had traveled first to Worcester, and met with Loyalists there, before going on to Marlborough. They were forced to leave when a hostile crowd threatened to attack the home where they were staying. Clearly disguise was not their strong suit.

"Stories" would have been a better choice of words than "facts," since we now know that the journal is not authentic.

Their next stop was Concord. Upon their arrival, the two asked for directions to the home of Daniel Bliss, a "friend of the government." (Subtlety was another skill they lacked.) Harvard-educated Bliss was a lawyer and a prominent citizen of the town. He believed that the Patriot cause was ill-conceived and doomed to fail, and he willingly provided De Berniere and Brown with as much information as he could.

The men returned to Boston and made a thorough report to General Gage. De Berniere accompanied the Regulars when they marched into Concord on April 19th and directed the soldiers to places where he had been told supplies were being stockpiled. He also kept a journal, which was discovered after the British Army left Boston a year later. The original journal does not make for exciting reading, so apparently someone — perhaps Luther Roby? — decided to give it a re-write: they used it as the basis for The Journal Kept by Mr. John Howe.

Unlike De Berniere, the fictitious Howe was an American working for General Gage. He was also a great deal smarter than De Berniere, using such clever disguises that townspeople told him anything he wanted to know. He, too, traveled to Worcester and Marlborough before arriving in Concord.

Somehow the young Mr. Howe managed to be everywhere April 19th, and he witnessed all the fighting.

Although Howe was merely "a beardless boy of twenty-two," he claimed that General Gage sought his advice. In words bound to delight American readers, Howe told the general if he marched "ten thousand regulars . . . to Worcester . . . not one of them would get back alive." As for seizing the stores he had just been shown in Concord, "five hundred mounted men, might go . . . in the night . . . and return safe, but to go with one thousand foot . . . the greater part of them would get killed or taken."

The Journal includes a variation of Paul Revere's famous ride. According to Howe, General Gage instructed him to "go on horseback . . . to carry letters to the tories," to inform them that Redcoats were about to march to Concord. He was then to "ride through adjacent towns" to see how he might help the Redcoats. Somehow the young Mr. Howe managed to be everywhere April 19th, and he witnessed all the fighting. The result was a change of heart: He switched sides — at least for the next few decades. When the fictitious hero wrote about the War of 1812, he tapped into New England's fierce opposition to the war. He was no longer loyal to either side; he became a "freelance" smuggler, staging a series of increasingly outrageous escapades, described in The Journal.

Just as the characters in the narrative fell for John Howe's ruses, so too readers, including a number of distinguished historians, long believed the journal to be authentic. In the early 1990s, a professor at Texas Christian University began to wonder if Howe's work was not just "too cute a narrative." Then he read the journal De Berniere had written and found striking similarities.

the British Army did send men out on reconnaissance trips, but most information came from the Loyalist inhabitants of every Massachusetts town.

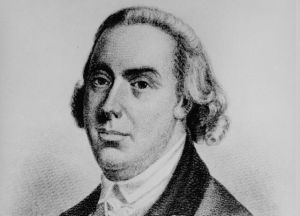

As De Berniere makes clear, the British Army did send men out on reconnaissance trips, but most information came from the Loyalist inhabitants of every Massachusetts town. Historians estimate that 10 to 15 percent of the colonial population was sympathetic to the British government. Loyalists came from all walks of life and supported the king and parliament for a variety of reasons. Chief among them: to oppose the Crown was treason.

Some Loyalists tried to keep a low profile. For example, John Flint, a former Concord selectman, wrote, "I think I shall be neutral in these times." It didn't work; Patriots had his name stricken from the jury list. Some Loyalists were ostracized; others were threatened with death, confined to house arrest, and, in the most extreme cases, tarred and feathered.

For Daniel Bliss, at whose home De Berniere and Brown stopped on March 20, 1775, the consequences of loyalty to the Crown were profound. When the townspeople saw that he was entertaining British spies, he was warned that he would not be allowed to "go out of town alive that morning." The British officers invited Bliss to leave with them. That night, he bid farewell to his family and left Concord never to return.

Like hundreds of Loyalists, Daniel Bliss and his family settled in Canada. In November 1780, he was tried in absentia and found guilty of "levying war and conspiring to levy war against the Government and People of this Province, Colony, and State." The Massachusetts legislature confiscated his estate and sold it at auction.

Links

The Museum of HoaxesLocation

This Mass Moment occurred in the Greater Boston region of Massachusetts.

Sources

The Minutemen and Their World, by Robert A. Gross (Hill and Wang, 1976).

"Specious Spy: The Narrative Lives—and Lies—of Mr. John Howe," by Daniel E. Williams, The Eighteenth Century, Vol. 34, No.3, 1993.

History of the Town of Concord, by Lemuel Shattuck (Russell, Odiorne, and Co., 1835).

Concord: Stories To Be Told, by Liz Nelson (Commonwealth Editions, 2002).